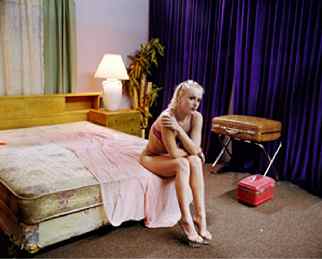

Here from cover to cover is Larry Sultan’s ‘The Valley’ for those who do not have access to a copy, and due to it’s limited number, this may be many of you.

An extensive excerpt of the text that accompanies the book ‘Nature is strange in the Valley’ is shown below and gives a little more insight from Sultan.

We would love to hear your thoughts, especially if this is the first time you have seen the book. Get involved in Twitter by using the #photobc hashtag, on Facebook here or in the comment section below.

Nature is strange in the Valley by Larry Sultan

It’s time for lunch. The sounds of clattering plates and muffled conversations drift upstairs. In cool, dark rooms, amber light glows through shades drawn in the middle of the summer day. Someone is napping fitfully. He’s bored rather than tired. He wakes up with a feeling of dread. In those first moments of confusion, he tries to assess which house he is in and what he’s doing there.

Downstairs, everyone has gathered in the large two-car garage. Folding tables have been set up with an array of cold cuts: stacks of wheat and rye bread, potato salad, paper bowls filled with cashews and M&M’s. There is a large platter of jumbo shrimp arranged in a circle around a head of lettuce. A tall woman wearing a T-shirt and thong spears one with a toothpick. Balancing paper plates filled with food, people drift into the back yard, a large grassy area with uninterrupted views of the San Fernando Valley. They look like friends and lovers having a Sunday picnic as they lie about in small groups in the few areas shaded by sycamore trees. To the far side of the yard, crew members are beginning to set up movie lights and a stand with a large silver reflector. On the lawn is a huge wind fan, and next to it Michael, the director, is talking with his wife, Julie Anne, who’s wearing a flowing pink dressing gown with a white fur collar. Her clear acrylic high heels are sinking into the grass, and he offers her his arm as she reaches back to pull off her shoe. Directly behind them, near the edge of the yard where the lawn ends abruptly in a vertical drop, stand 5-foot-tall letters cut from plywood, painted white and anchored in the ground with diagonal supports. DOOWYLLOH. It takes a moment to make sense of it, but then it’s as clear as the day: Facing out toward miles of subdivisions and malls, a miniature version of the sign — Hollywood in the Valley.

The house is a big, two-story “old hacienda”–style place, built sometime in the 1970s. When I called to get the location for today’s shoot, the production assistant assured me that I would like it. “You’ve really got to see this house: high ceilings, enormous rooms, a spiral staircase. It’s a real mansion with an incredible view.” In the past 10 years, homes in the Valley have become the preferred locations for adult-film companies, which rent them from their owners for the two to three days that it takes to make a porn film. In reality this house is just an oversize variation of a tract home, with sliding glass doors and cottage-cheese ceilings. It’s been customized with dark wood paneling, overbearing stonework, marble counters and other features that give it the appearance of the “good life,” of wealth and taste. Wandering from room to room, I get the feeling that something went wrong, that the owners have left suddenly in the middle of the night. They’ve abandoned the entertainment center with their mega-TV and sound system, the exercise room that has been converted into an office, the bleak master-bedroom suite with its Jacuzzi and statuary. They’ve left behind some evidence, personal effects, notes by the phone, shopping lists and “things to do” stuck to the refrigerator. In the living room there hangs a formal portrait of the family standing in the back yard in late-afternoon light. It’s been printed on textured paper and framed in gold to give it the appearance of an oil painting. Throughout the house there are more casual photographs, 8-by-10s of smiling sons and daughters, the family dogs, the big anniversary party on the cruise ship. They cover all available surfaces and stare down at us from nearly every wall in the house.

A few years after we moved from our first house in working-class Van Nuys into a new house in Woodland Hills at the far western edge of the Valley, my mother hired an interior decorator. With marble-tile floors, Formica kitchen counters, and 12-foot fireplaces in the den and living room, the house felt cold and needed to be “cozied up.” The decorator was from South Carolina, and, as my father would say, she was “quite a dish.” She had piles of brassy red hair and wore tight white pants that revealed faint traces of either beige or pink panties. I remember my fascination with her lipstick, which covered her mouth well beyond its natural borders. She had my mother completely under her spell.

It didn’t take long to see the results of her handiwork. She painted a grape vine on the kitchen wall and attached real rubber grapes to its tendrils. She was crazy about gold leaf and applied it freely, on the upholstered footstools, the end tables, the oversized candleholder standing next to the sofa, and on a big wooden box that sat on the coffee table with no discernable purpose. She brought in bright green shag carpets and a massive coffee table adorned with gold and black paint, and she filled the gaps on our bookshelves with Reader’s Digest compilations. But the real pride and joy for all of us was the painting she made that hung over the length of our flesh-colored Naugahyde sectional: a sweeping panorama of an Italian landscape. In the foreground jesters danced with bare-breasted women in the courtyard of imagery Florentine villa. It was bold and magical — too bold, it seems. After a year or two my mother had it cut into two parts and each was reframed. One piece appeared in the dining room and the other in the living room, where no one ever ventured.

The entire house vibrates, shaking as if a dozen overloaded washing machines were stuck on the spin cycle. Exaggerated moans, groans and screams erupt from the back rooms. From the crescendo I can tell that the director has called for the FIP (fake internal pop) shot. I half expect the next-door neighbors or the police to rush over and bang on the doors to see if everything, everyone is all right. But then it grows quiet.

The talent get up from their positions and reach for bottles of cool water and dry towels. The cameraman is distracted and forgets to turn off the camera. It dangles from his arm, relaying a series of random images of the interior landscape of the bedroom over to the monitor in the next room: the junction of wall and ceiling, the corners of dressers, a chair and parts of bodies, under the bed. It’s as if someone, overcome by excitement and intense desire, is crawling around the room on his hands and knees interrogating every object and surface for its secrets.

Being on a film set is a bit like those endless summer days of high school: hanging out, waiting for something to happen; snacking, even when you’re not hungry; napping in the middle of the day. Invariably I end up standing around in the back yard.

Nature is strange in the Valley, a chaotic mix of unrelated trees and plants that share the same space. Palm, spruce, eucalyptus, poplar and pine, all in neighboring yards, each seeming to generate its own microclimate. There is a peculiar quality of silence that hovers over these streets, like an invisible dome that insulates it from the noises of the working life of Los Angeles. It filters the light and softens the edges of things, giving them a glow like a landscape seen through a thin layer of gauze. The heavy air becomes a medium for amplifying the small sounds that occasionally reverberate throughout the neighborhood. A car door closes; someone wheels in the garbage can; a few kids yell at each other in a back yard; a roofer off in the distance hammers for a few seconds, stops and then starts up again. Standing in the back yard listening to these sounds has the effect of slowing down time, elongating the space between the random sonic events.

The cord to the refrigerator is pulled from the wall socket; the air conditioner is turned off in the heat of the day; toilets go unflushed; conversation stops. Everything is still except the wild knot of bodies writhing on floors, couches and tables.

I walk around on tiptoe, stand in hallways and lean against walls. I want to see but don’t. I pretend not to look. Like an argument or a fistfight, the scene grabs my attention, pulls me in.

The event of filming creates a sexualized zone in which the gestures, rituals and scenes of suburban domestic life take on a peculiar weight and density. The furnishings and objects in the house, which have been carefully arranged, become estranged from their intended function. The roll of paper towels on the coffee table, the bed linens in a pile by the door, the shoes under the bed are transformed into props or the residue of unseen but very imaginable actions. Even the piece of half-eaten pie on the kitchen counter arouses suspicion.

The production assistant comes in and tells everyone on the set that we’re not allowed to park on the street in front of the house. She tells us to park farther up the block or on the next street over. As if in a fire drill, we pour out of the house and stand somewhat dazed in the glaring light that bounces off the driveway in front. In the minute or two it takes to walk to our cars, the sidewalk hosts a brief spectacle: a parade of women in 6-inch heels and tight, skimpy clothes and men with shaved heads and tattoos, all laughing, talking loudly and smoking cigarettes. I look across the street to see if neighbors have come to their windows or out onto their front porches to watch, but they haven’t. The few people who are at home stay deep inside their houses.

I park way up the street, and as I walk from my car I meet up with Claudia, a woman in her early 20s who is just getting started in porn films. It feels slightly strange to be walking the street in the middle of the day, like we’re either intruders or a father-daughter team of Jehovah’s Witnesses. She tells me that she grew up in this neighborhood and that her best friends lived just a few blocks away. She tells me that they would hang out together all summer long in the pool house in the back yard, watching TV, getting stoned. They were known as the Big Titty Committee. I ask her if she went to the local high school, Taft High, where I went to school. “Yeah,” she says, “but only for a year. Then I was sent away to school in Colorado, one of those survival-type programs. I was a bad girl. I guess I still am.”

There was a girl my age who lived in the corner house at the end of the street and who went to the same high school as I did. She had a remarkable body and a very bad complexion. To solve some of the social problems caused by her acne, she reportedly gave sexual favors to the jocks and the more popular guys at Taft High. Late in the afternoon when school was out I would see all these guys milling around her house and lining up at the front door. There was Gary H., the quarterback, and Barry A., the big overweight linesman. I would endlessly imagine what these guys got to do with her. I pictured them in all possible combinations.

Once while we were waiting at the corner for the school bus, she glanced over at me and made an obscene gesture: Her arms at right angles to her body, she began pumping them in and out. It confused me and I had no idea how to respond to her. But I took it as a sign and later that day I got up my nerve and walked down to her house. I was worried that in order to have sex I might have to kiss her. All I could picture were her blackheads and enlarged pores, a troubling image and an omen of a bad performance. But it was too late; I was already knocking on her front door. When she opened it, she was taller and more imposing than I had remembered. She was wearing a flower-print dress that lent her an unexpected air of modesty as well as maturity. She stared at me for a few seconds, like she didn’t know who I was. Then a strange smile or smirk appeared on her face. “What do you want?” I just stood there feeling the blood drain from my face into my hands that were dangling at my sides. I couldn’t begin to find the words.

It’s Wednesday, the middle of the week, and everyone is taking the day off. Men and women return home from work early, bringing carloads of friends with them. The streets are lined with black SUVs, Cadillacs and Corvettes. There’s no place to park.

It looks like an interracial block party, with Latinos and African-Americans wheeling suitcases filled with sexy costumes up driveways and into back yards. Deliverymen, saleswomen, and neighbors who have lost their dogs or who need a cup of sugar come to the door and are invited in for lunch. There’s nothing like a good, hot lunch in the middle of the day, pasta with sausage and peppers and chicken and plenty of sauce. The television is on, but the volume is turned way down. In the back yard, the automatic pool sweeper drifts around the pool making a swishing noise, almost like a muffled rain bird: sh sh sh sh. The pool looks like a blue oasis sparkling in the heat. People sit around in small clusters and joke, make small talk and eat. Slowly they lose their inhibitions. A young woman leans over and asks if her breath smells; a man stands up and casually takes off his clothes. Someone is nibbling on someone else’s neck.

What could be better? A lazy afternoon in the suburbs with all the time in the world to enjoy the small things and to spend a day in another’s arms. A day that is punctuated not by noisy children and errands but by the urges and fantasies of the people gathered together here. They raid the refrigerator and put whipped cream, butter and even mustard on each other’s naked bodies. They rub one another into a frenzy. They crowd into the master bedrooms and spill out onto the kitchen floors and onto the patios and into the pools that look just like our neighbors’ pools, like our pool, and do the stuff of daydreams.

It’s a day when no one turns away from another, when tentative glances and awkward first moves are met with passionate approval. Everyone is seen, and held, and longed for. One’s clumsy body knows exactly what to do. It is a day when betrayals are overlooked or are mutually forgiven.

But at the end of it all, these people do not retire to the living room to watch their favorite TV programs together. Nor do they go upstairs to bed. Instead they pack up their high heels, fancy underwear and sweaty T-shirts, and they carry them to their cars. They pat the backs and kiss the cheeks of those who earlier in the day were such intense lovers. Exhausted, they drive across the Valley to their apartments.