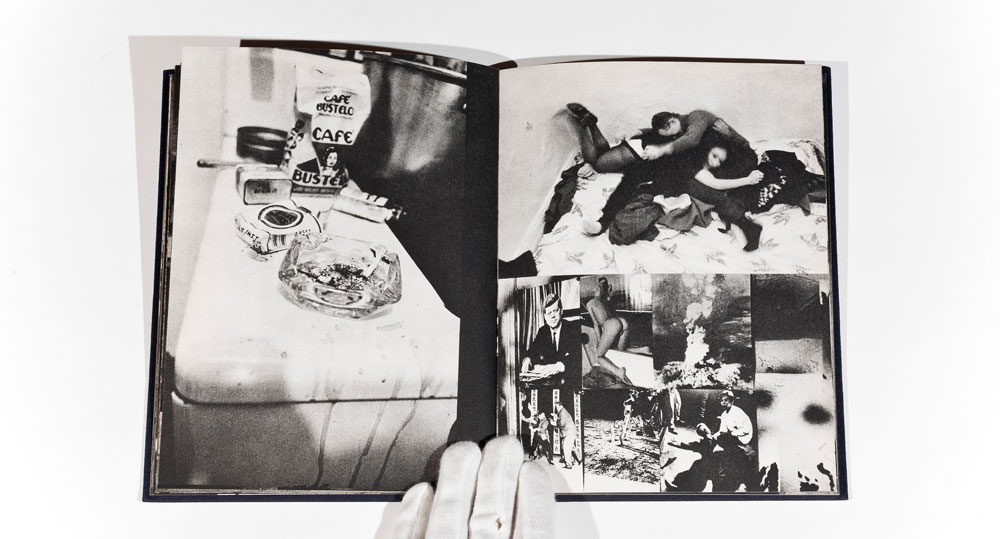

As well as showing Invisible City in its entirety here, we see that the text is just as important to try and get a sense of the book and Schles’ vision. So here is the text featured in the book alongside the full video for your viewing pleasure!

Opening text:

Cities are a product of time. They are the molds in which men’s lifetimes have cooled and congealed, giving lasting shape, by way of art, to moments that would otherwise vanish with the living and leave no means of renewal or wider participation behind them. In the city, time becomes visible: buildings and monuments and public ways, more open than the written record, more subject to the gaze of many men than the scattered artifacts of the countryside, leave an imprint upon the minds even of the ignorant or the indifferent. Through the material fact of preservation, time challenges time, time clashes with time: habits and values carryover beyond the living group, streaking with different strata of time the character of any single generation. Layer upon layer, past times preserve themselves in the city until life itself is finally threatened with suffocation… Lewis Mumford The Culture of Cities

Back of the book text:

Steadily, for the past generation, a transformation has been going on in every department of thought: a re-location of interest from mechanism to organism, a change from a world in which material bodies and mechanical motion alone were real to a world in which invisible rays and emanations, in which human projections and dreams, are as real as any immediately visible or external phenomenon – as real and on occasion more important.

Lewis Mumford, The Culture of Cities

A man becomes confused, gradually, with the forms of his destiny; a man is, by and large, his circumstances. More than a decipherer or an avenger, more than a priest or a god, I was one imprisoned. From the tireless labyrinth of dreams I returned as if to my home to the harsh prison.. I blessed its dampness, I blessed its tiger, I blessed the crevice of light, I blessed my old suffering body, I blessed the darkness and the stone.

Borges Labyrinths

All is imaginary – family, office, friends, the street, all imaginary, far away or close at hand, the woman; the truth that lies closest, however, is only this: that you are beating your head against the wall of a windowless

and doorless cell.

Kafka Diaries (1921)

This metropolitan world then, is a world where flesh and, blood is less real than paper and ink·and celluloid. It is a world where the great masses of people, unable to have direct contact with more satisfying means of living, take life vicariously, as readers, spectators, passive observers: a world where people watch shadow-heroes and heroines in order to forget their own clumsiness or coldness in love, where they behold brutal men crushing out life in a strike riot, a wrestling ring or a military assault, while they lack the nerve even to resist the petty tyranny of their immediate boss: where they hysterically cheer the flag of their political state, and in their neighborhood, their trades union, their church, fail to perform the most elementary duties of citizenship.

Living thus, year in and year out at second hand, remote from the nature that is outside them and no Ie remote from the nature within, handicapped as lovers and as parents by the routine of the metropolis and by the constant specter of insecurity and death that hovers over its bold towers and shadowed streets living thus the mass of inhabitants remain in a state bordering on the pathological.

[Nb – The quote continues, but I did not include this part in the book, although it might be interesting to see it here:] – Ken Schles

They become the victims of phantasms, fears, obsessions, which bind them to ancestral patterns of behavior. At the very point where super-mechanization takes hold of economic production and social intercourse, a treacherous superstition, a savage irrationality, reappear in the metropolis. But these reversionary modes of behavior, though they are speedily rationalized in pseudo-philosophies, do not remain on paper: they seek an outlet. The sadistic gangster, the bestial fascist, the homicidal vigilante, the law-offending policeman burst volcanically through the crust of metropolitan life. They challenge the dream city with an even lower order of ‘reality’.

Lewis Mumford, The Culture of Cities (p.258)

…reality itself, entirely impregnated by an aesthetic which is inseparable from its own structure, has been confused with its own image. Reality no longer has the time to take on the appearance of reality. It no longer even surpasses fiction: it captures every dream even before it takes on the appearance of a dream. Schizophrenic vertigo of these serial signs, for which no counterfeit, no sublimation is possible, immanent in their repetition – who could say what the reality is that these signs simulate?

Jean Baudrillard, Simulations

All he wanted was to hold the photograph in his fingers again, or at least to see it.

‘It exists!’ he cried.

‘No,’ said O’Brien.

He stepped across the room. There was a memory hole in the opposite wall. O’Brien lifted the grating. Unseen, the frail slip of paper was whirling away on the current of warm air; it was vanishing in a flash of flame. O’Brien turned away from the wall.

‘Ashes,’ he said. ‘Not even identifiable ashes. Dust. It does not exist. It never existed.’

‘But it did exist! It does exist! It exists in memory. I remember it. You remember it.’

‘I do not remember it,’ said O’Brien.

Winston’s heart sank. That was doublethink. He had a feeling of deadly helplessness. If he could have been certain that O’Brien was lying, it would not have seemed to matter. But it was perfectly possible that O’Brien had really forgotten the photograph. And if so, then already he would have forgotten his denial of remembering it, and forgotten the act of forgetting. How could one be sure that it was simple trickery? Perhaps that lunatic dislocation in the mind could really happen: that was the thought that defeated him.

O’Brien was looking down at him speculatively. More than ever he had the air of a teacher taking pains with a wayward but promising child.

‘There is a Party slogan dealing with the control of the past,’ he said. ‘Repeat it, if you please.’

‘”Who controls the past controls the future: who controls the present controls the past,”‘ repeated Winston obediently.

George Orwell, 1984