Shortly after our first post on Avedon’s ‘Observations’, Katja Anderson got in touch to offer her own contribution to this months book, and we are really pleased she did: below is Katja’s piece which offers background, comment, deconstruction and a few ‘behind the scenes’ facts, a great read. (Don’t have a copy of ‘Observations’? – Take a look at our video)

Katja Anderson – Richard Avedon’s ‘Observations’

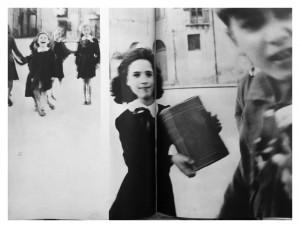

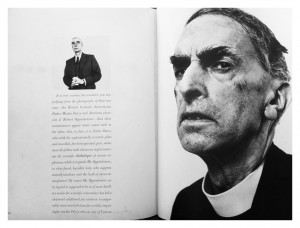

In 1959, lovers of photography and popular fiction alike were eagerly awaiting the publication of Observations, a collaborative effort between Richard Avedon and Truman Capote. Avedon had taken the photographs, all portraits, an interesting departure for a man known primarily as a fashion photographer. Capote, an old friend, was asked to write the text, while Alexey Brodovitch, then the former art director of Harper’s Bazaar and the man who had made certain Avedon would work for the publication, was responsible for the layout and cover art. It was an interesting time for anyone associated with Harper’s Bazaar, which included Capote. While never a staff writer, he had written an article when in his early twenties, a relatively obscure writer of short stories. The fiction editor had sent him to New Orleans, accompanied by Henri Cartier-Bresson. Capote commented: “I’ve never worked so hard and I never want to again.”

Harper’s Bazaar had some of the most talented people in the business on the masthead, ranging from Brokovitch to the brilliant editor-In chief Carmel Snow; Avedon later claimed that everything he knew he had learned from her. She hired him, Brodovitch having sung his praises. Avedon was twenty-two, a high school dropout who served his country during World War II by working as a photographer, using his Rolleiflex (a going away present from his father) to take one I. D. photograph after another for two years. After returning to New York, he enrolled at the New School, where he was taught by Brodovitch. Brodovitch, struck by similarities between Avedon’s work and that of Martin Munkasci, an eminent photographer on the Harper’s Bazaar payroll. It was the real reason Carmel Snow hired him. Both men depicted models smiling, laughing, exceptionally energetic, constantly in motion (as Avedon himself was).

Diana Vreeland was another brilliant member of staff, a fact that understandably evaded Avedon when they first laid eyes on one another. As he recalled many years later: “Vreeland returned to her desk, looked up at me for the first time and said, ‘Aberdeen, Aberdeen, doesn’t it make you want to cry?” He continued with: “Well, it did. I went back to Carmel Snow and said, ‘I can’t work with that woman. She calls me Aberdeen.’ And Carmel Snow said, ‘You’re going to work with her.’” It was the beginning of a forty-year professional relationship, as well as a close friendship. Avedon and Vreeland inspired the Audrey Hepburn film Funny Face, Dick Avedon hired as adviser, helping Fred Astaire portray his alter-ego Dick Avery.

That was in 1956; the film was released the following year. Avedon and Capote had been friends for years (“Dickiboo”). Near-exact contemporaries, both attained

fame early, Capote with his bestselling first novel, Avedon as a photographer, sufficiently well known for Life magazine to publish page after page of his portraits of Broadway stars, referring to him by surname. But the photographs were lacklustre. Good enough for a widely circulated magazine aimed at the average American, but not Avedon. By the early Fifties, his style had changed dramatically by eliminating every superfluous detail, as well as exploiting the Rolleiflex, capable of producing “a hallucinatory sharpness.”

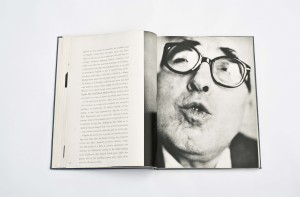

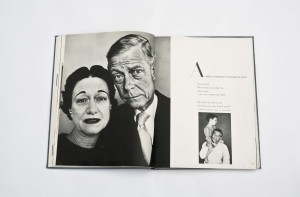

Avedon was as driven, as intense as Capote was relaxed. He continued to work on portraiture, placing subjects against a background of medium or lighter hue. By 1957, if not earlier, he had become skilled at saying exactly the right thing to elicit an emotional response. Everyone, particularly celebrities, wore masks in public and Avedon was determined that the masks would, if not fall off completely, at least slip. His portrait of Marilyn Monroe exposed a lost, vulnerable woman, oblivious to her blonde beauty and highly sexual presence. Perhaps the expression was fleeting, perhaps not, but the challenge for Avedon was to capture it on film as quickly as possible, not to mention eliciting it; while Avedon sought to have good relationships with his models, even taking the trouble to discover the food and music they liked, a celebrity sitter was a very different matter. Usually, there was no relationship between celebrity and photographer, and while Avedon which buttons to press as far as the models were concerned (he tended to use the same models over and over) there was no such luxury with a stranger, no matter how famous. Sessions were brief, about ten minutes long, so Avedon would ask a provocative question. Or make a statement certain to elicit an emotional response. While photographing the Duke and Duchess of Windsor, he casually mentioned a taxi driver hitting a dog earlier. The masks slipped, if only for a moment; Avedon clicked away on the Rolleiflex and revealed the Windsors as the sad, tired couple they had become.

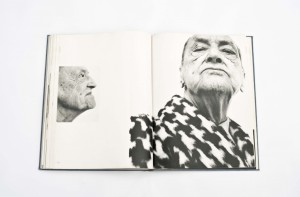

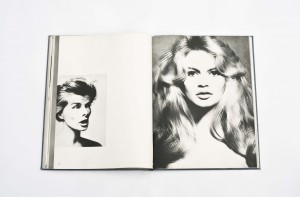

Brigitte Bardot was another matter, merely looking at the viewer, too characteristically languid to be surprised. Marella Agnelli was positively tranquil, serenely gazing into the camera, the only sign of life in her limpid, faintly glowing eyes. Including her portrait in Observations was surprising, as was that of American social figure Barbara ‘Babe’ Paley. Both Marella and Babe were best known to those who read fashion magazines and gossip columns. And there was little room to spare in the book; images fought for space. By 1959, Avedon had such an impressive body of work (in terms of quality as well as quantity) that rejection was rather more common than inclusion. As Brodovitch was responsible for the layout, one suspects he advised his former protege. One suspects, too, that Capote pressed for the portraits of Marella and Babe (two of his closest friends) to be chosen. A travel diary kept by a seventeen-year-old Grand Tourist inspired his text, likening the women to swans. A lovely, exceptionally graceful image, but one reads on. Thanks to a wealthy man, “…a husband, a father”, these women created an illusion of beauty, the ‘swan illusion’, a substitute for the real thing, so powerful, so convincing that everyone who lays eyes on the swans is convinced as well. A backhanded compliment if there ever was one, but one with more than a grain of truth, as is the case with many observations.